By Dr. Brian Frederking, Class of 1990

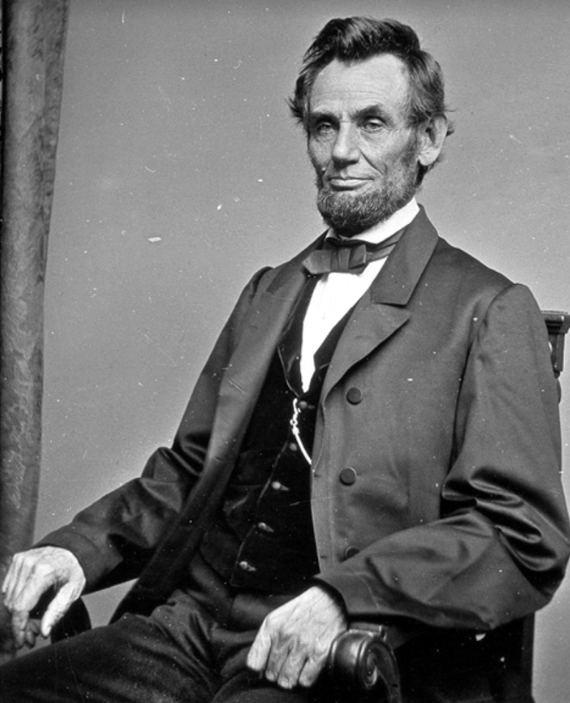

Title photo of Abraham Lincoln from Common American Journal

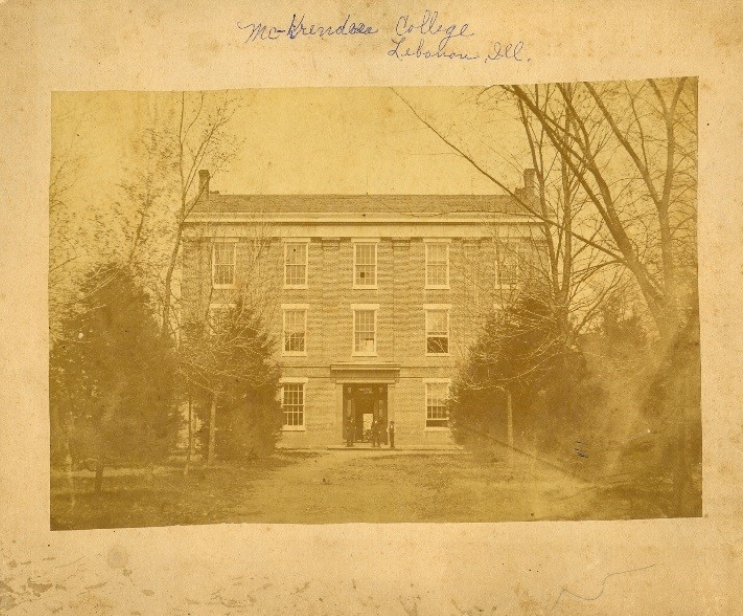

McKendree University will be 200 years old in 2028. One amazing part of its illustrious and resilient history is the many interactions between early McKendree figures and the great Abraham Lincoln. The cause of abolitionism symbiotically forged the trajectories of the young Methodist college and the future United States president. In ways large and small, McKendreans were part of Lincoln’s life – as religious inspirations, political opponents, biographers, wartime emissaries, coworkers, bodyguards and confidantes to the American hero.

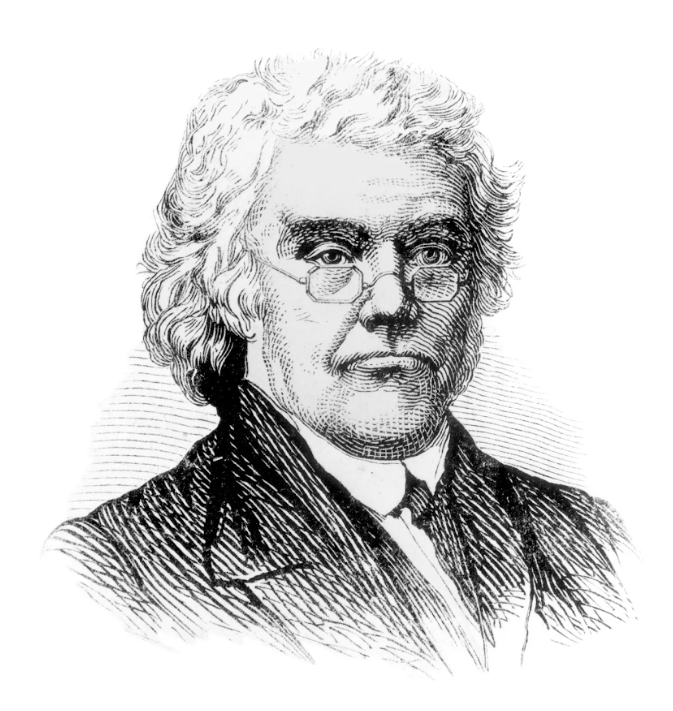

The relationship between McKendree and Lincoln began in 1832 when Lincoln was a 23-year-old store clerk and rail splitter who ran for the state legislature. His first political opponent was Peter Cartwright, a prominent Methodist preacher. As the Presiding Elder of the Illinois Methodist Conference, Cartwright was crucial to the 1830 decision that the conference adopt the Lebanon Seminary as its official school. As a manager of the Lebanon Seminary, Cartwright made the historic motion to change its name to McKendree College in honor of Bishop William McKendree, who had donated 480 acres of land to support the school.

The Methodist Episcopal Church was staunchly abolitionist, and Cartwright had an unusual political career as an anti-slavery Democrat. He was elected to the state legislature in 1828 to fend off the growing movement in Illinois to amend the state constitution and legalize slavery. After an unsuccessful run for governor in 1830, Cartwright ran again for the state legislature in 1832. The famous preacher defeated the young and lesser-known Lincoln for that seat, the only election based on citizen voting the future president ever lost.

The next year, Lincoln attended a camp meeting outside Springfield where Peter Akers preached for three hours. Akers was another prominent Methodist minister who later that year became the first president of McKendree College. His favorite sermon theme was the evil of slavery, and he was an important figure in the Methodist Church as it expanded into the South. In 1844, he helped draft a resolution censuring a Georgia bishop for owning slaves. When the resolution passed, the Southern conferences left and formed their own church.

Lincoln called Akers the greatest preacher he ever heard.1 At the 1833 camp meeting, Akers vigorously applied Old Testament prophecy and predicted that God would overthrow the sinful world and end slavery. He argued that his audience would live to see it, and that those who would accomplish God’s work were right there on the campground! On the way home that night, Lincoln told his companions that he could not stop thinking about the possibility that Akers was referring to him.2

With Akers as president, McKendree gained a state charter in 1835. Since granting a charter to a private, religious college was politically controversial at the time, it included some conditions: 1) McKendree could not establish a “theological department”; 2) McKendree had to accept students from all religious denominations; and 3) McKendree could own no more than 640 acres of land. Four years later, McKendree wanted a charter without curricular or land restrictions. Lincoln was then in the state legislature and supported the more generous charter, which would go into force when the Board of Trustees accepted it.

After Lincoln helped secure the successful vote on January 16, 1839, he urged McKendree’s fiscal agent Benjamin Cavanaugh to accept it quickly, concerned that opponents might realize the generosity of the charter and muster the votes to rescind it. Cavanaugh heeded Lincoln’s advice and rode 60 miles on horseback through mostly wilderness from Vandalia to Lebanon in 12 hours to notify McKendree leaders. Nine days later – lightning fast in those days – the Board of Trustees held an emergency meeting to accept the charter, which remains in effect today.

Lincoln hired Henry Horner (Class of 1841) to his law practice immediately after his graduation from McKendree. Henry’s grandfather Nicholas Horner and his father Nathan Horner were the largest original donors to the Lebanon Seminary in 1828. His father Nathan Horner served on the Board of Trustees for over 40 years, and Henry Horner was one of the first Lebanon Seminary students in 1828. Horner credited Lincoln for advancing his legal career – he became a prosecutor, the first mayor of Lebanon, and the Chair of the Law Department at McKendree from 1865-1889, shepherding the education of many of McKendree’s most prestigious graduates.

Lincoln squared off against Cartwright again in 1846, when both ran for the United States Congress. Lincoln was 37, and Cartwright was 62. Cartwright questioned Lincoln’s religious faith, accusing him of Deist beliefs. Lincoln argued that Cartwright’s education and prohibition policies threatened the separation of church and state. Lincoln’s stature was greatly enhanced by his victory over the famous preacher, and that election propelled his political career. Their relationship softened in 1859 when Lincoln defended Cartwright’s grandson in a murder trial and won an acquittal with Cartwright as the star witness. Throughout Lincoln’s presidency, Cartwright defended Lincoln’s character and even his religious beliefs.

John Locke Scripps (Class of 1843) played a huge role in electing Lincoln to the presidency. Scripps was the editor of the Chicago Tribune and traveled with the future president during the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858. Scripps became an important ally who co-wrote with Lincoln a campaign biography in 1860.3 With no television or radio, campaign biographies were important tools of political communication, and it swayed enough voters in the 1860 election that Scripps received some credit for Lincoln’s election. It introduced a relatively unknown Illinois politician to the country and established the enduring legend of a moral crusader against slavery rising from poverty and a troubled childhood. With financial support from the anti-slavery movement and Horace Greely publishing excerpts in the New York Tribune, Scripps’ biography had a first printing of over a million copies.

Risdon Moore (Class of 1850) was a McKendree professor who knew Lincoln through his father, a friend of the future president in the 1830s. Professor Moore took McKendree students to see Lincoln after a campaign event on August 8, 1860. Moore and Lincoln recalled a story of a wrestling match between Lincoln and Lorenzo Dow Thompson at Beardstown during the Black Hawk War in April 1832. Lincoln was the captain of one company of volunteers, and Moore’s father was the captain of another. Both wanted to set up camp on the same ground, and they decided that a wrestling match would determine the outcome. Lincoln represented his company, and Moore’s father chose Lorenzo Dow Thompson. Lincoln recalled the story:

I felt of Mr. Thompson, the St. Clair champion, and told my boys I could throw him and they could bed where they pleased. You see, I had never been thrown or dusted as the phrase then was…I tell you the whole army was out to see it. We took our holds, his choice first, a side hold. I then realized from his grip for the first time that he was a powerful man and that I would have no easy job. The struggle was a severe one but after many passes and efforts, he threw me…gentleman, that man could throw a grizzly bear.4

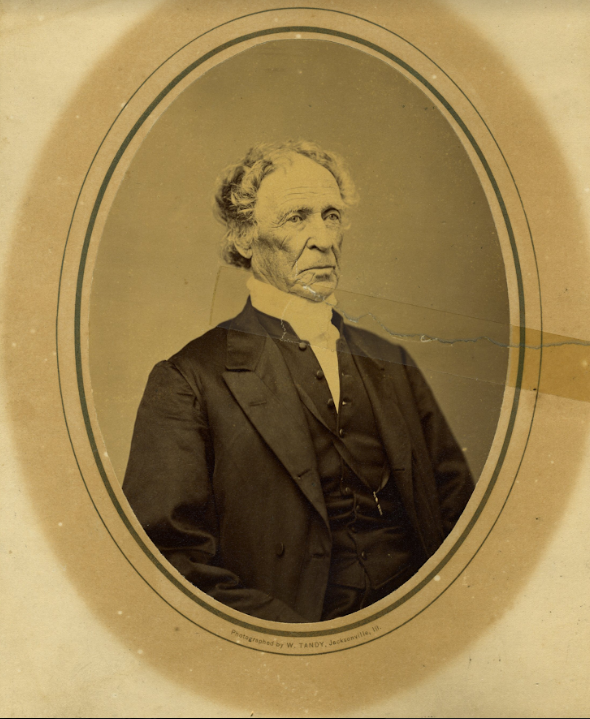

When Lincoln won the presidency, he asked his friend and confidant Bishop Edward Ames several times to take a seat in his cabinet. Ames was the first principal of the Lebanon Seminary in 1828 as a young man and later became a Methodist bishop. While Ames refused the cabinet positions, he did serve on a commission to exchange prisoners during the Civil War. When the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1864 voted to confiscate property from the Methodist churches in the South, Lincoln’s War Department put Ames in charge of Northern Methodists following the victorious Union army into conquered territory. Ames himself traveled down the Mississippi River to carry out the church’s policy in New Orleans.

McKendree College enthusiastically supported Lincoln and the abolition of slavery during the Civil War. After Lincoln called for 300,000 volunteers in the spring of 1862, all twelve graduating seniors used their commencement address to urge McKendreans to fight for the Union, advocating, in the words of one, “the duty of citizens to engage in righteous warfare when their country needed their service.” A majority of McKendree students then volunteered. So many signed up for the 117th Illinois Voluntary Infantry in September 1862 that it was known as the “McKendree Regiment.” Its leaders were Professors Risdon Moore and Samuel Deneen (Class of 1854). Four other McKendreans served as generals during the war: James Wilson, Wesley Merritt, Jesse Moore (Class of 1842), and John Rinaker (Class of 1851).

Lincoln was acutely aware of the staunch support of the Methodist Church in favor of his political, military, and moral goals. During the war, he said:

[I]t may fairly be said that the Methodist Episcopal Church, not less devoted than the best, is, by its greater numbers, the most important of all. It is no fault in others that the Methodist Church sends more soldiers to the field, more nurses to the hospital, and more prayers to Heaven than any. God bless the Methodist Church—bless all the churches—and blessed be God, Who, in this our great trial, giveth us the churches.5

Lincoln asked two McKendreans to perform vital wartime services. One was the extraordinary J. Wesley Jones (Class of 1844), whom Lincoln had hired into his law practice. When the California gold rush hit, Jones traveled west and struck it rich. His sketches of the California plains were published in Harper’s Magazine and are now in the National Archives in Washington DC (and the Holman archives!). After returning from California, he and his brother William (Class of 1852) started a women’s college in Evanston, which eventually merged with Northwestern University. During the Civil War, Jones organized his own regiment. Lincoln, trusting him from his Illinois law practice, asked Jones to supervise his White House bodyguards. (Unfortunately, Jones’ forces were no longer in operation when John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln in 1865.)

The second McKendrean was James Jacquess, a circuit-riding Methodist minister in Illinois Lincoln knew who earned a master’s degree from the college in 1848. During the war, Jacquess organized a “preacher’s regiment” known for its large number of clergy and Methodist men. In 1864, Lincoln sent Jacquess as an unofficial emissary on a dangerous mission to meet with Confederate president Jefferson Davis. Jacquess passed along Lincoln’s peace plan: the emancipation of slaves, compensation to slave owners, and amnesty for all rebels. Davis rejected the plan, and the wide dissemination of the peace overture helped Lincoln win reelection, the final great turning point of the war.6

A final, strange, and indirect connection to Lincoln concerned a student in McKendree’s preparatory school and a future graduate named Richard Thatcher (Class of 1878). He enlisted on his fifteenth birthday as a drummer boy. Private Thatcher was captured near Atlanta in 1864 and imprisoned in Andersonville. He loaned his Bible to another prisoner and the two organized daily prayer sessions. They eventually escaped from the prison and, with the help of slaves, made their way to the safety of Union forces. The other prisoner was Boston Corbett, who would later shoot John Wilkes Booth after Booth assassinated Lincoln.

References

1 Savage, G.S. 1910, “Pioneer Congregational Ministers in Illinois,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol. 3, p. 4.

2This account is told in W. N. McElroy, Central Christian Advocate, Sept. 9, 1896. It is also in Ida M. Tarbcll, The Life of Abraham Lincoln (New York, 1900).

3 Scripps, John Locke. 2010. Vote Lincoln! The Presidential Campaign Biography of Abraham Lincoln. Sacramento, CA: Boston Hill Press. Expanded Edition.

4Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher. 1996. Recollected words of Abraham Lincoln, Stanford University Press, p.232.

5Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Volume 7. Quoted on May 18, 1864. University of Michigan.

6Burnette, Patricia B. 2013. James F. Jaquess: Scholar, Soldier, and Private Agent for President Lincoln: MacFarland Press.