By Nathan Ploense, Contributing Writer

Driving through Lebanon on a late fall afternoon usually yields little to no excitement. During summer the brick-laid road can feature fairs, car shows or families heading to Dr. Jazz or the surrounding stores, but a street which usually has vibrant colors and an essence of life becomes grey-washed as winter sets in and the temperatures drop. There is not much to see during these days except maybe a stray cat or someone contemplating donning a jacket to compensate for the wind-chill.

With a passing glance while I drove the bland roads one day, a man appeared on a street corner, standing with a full canvas and easel, painting in the transitioning season, morning through the afternoon, wearing a ushanka hat and covered with oil paints.

As 2017 wore down, the painting gained the colors the road had lost but word of who he was or why he was there never came up.

New Years passed and 2018 took hold over McKendree. A poster hung all over campus depicted a man in a ushanka hat that would be featured at The McKendree Gallery of Art. The show’s title is: “OF: paintings, prints and sculptures by Michael Neary.”

by: Michael Neary

A public reception was about to take place where the community would have the opportunity to meet the artist himself.

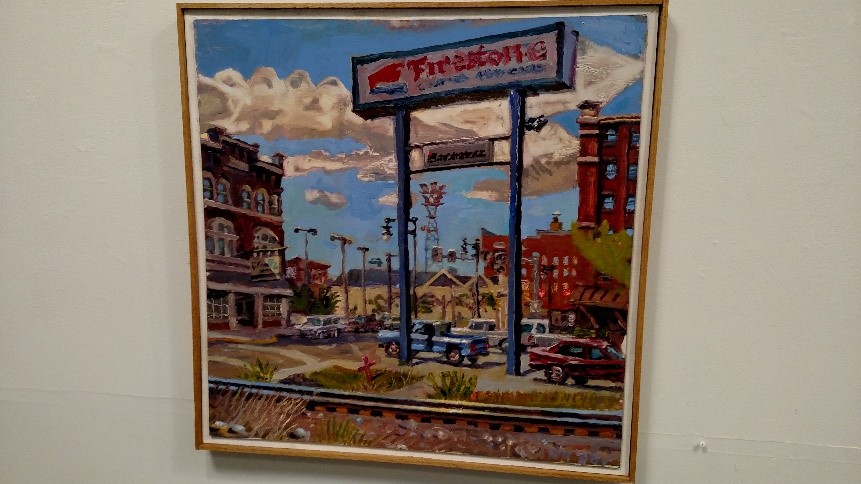

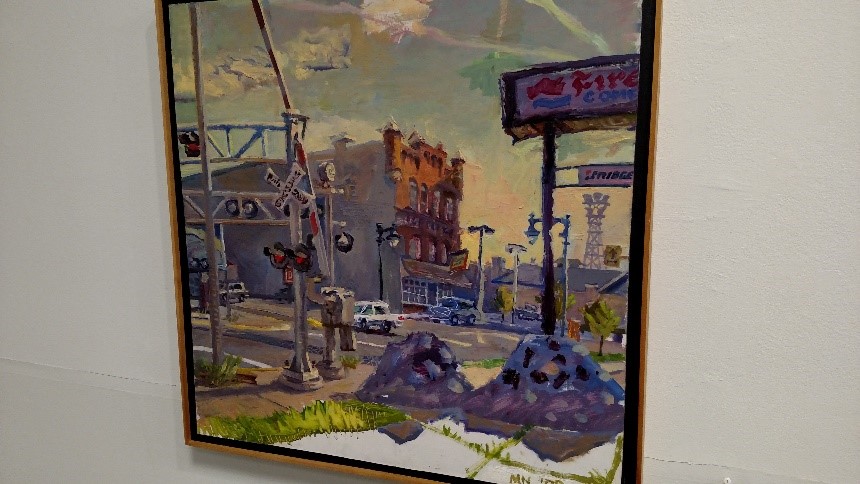

As I stepped into the gallery, it was calm but busy with those appreciating the pieces on the wall and talking with Neary as if they were old friends. I can’t say that art appreciation is one of my strong suits but this work, even on the surface, was familiar, like it had captured images from my home town. Sculptures were spatially interesting, the materials a bit unorthodox and the prints begged to be examined for deeper meaning or a message. One of the most defining features in the work was his use of slight perspective change. Slight shifts of position or the time of day or a few steps in the other direction became visible, often allowing the viewer to question perception.

Born in Bloomington, Ind., Michael Neary had a relatively middle-class upbringing, but his father’s business allowed the family to move to many different places. He grew up in Detroit, San Diego, New Orleans, Seattle and Maryland before eventually leaving home to seek out a college degree.

In 1975, he graduated with a Bachelor’s in Fine Arts. “When I was first going to college I was trying to do something sensible and it just didn’t take.” Leaving college momentarily and working around he decided to return to school and take art classes because they “made [him] feel engaged,” a feeling most McKendree students are familiar with.

One of his first jobs while going through college was with an uncle doing mining construction in Pennsylvania. Working on a team to dig out a slope below the coal layer and then placing explosives to remove the unwanted material was physical and interesting work. Neary ended up getting hurt on the job in a non-severe manner and was able to have a few months off where he pulled together a portfolio and set off to grad school. He would eventually receive his Master of Fine Arts degree and move on to a career of painting.

“I don’t necessarily have to have and picturesque locations or subject matter. I look for various situations or motifs that have certain spatial conditions that appeal to me. Kind of, possibilities that change to create compositional events,” Neary says. Spending time in one location for an entire summer and pouring in work to several pieces about the space, Neary uses his surroundings and learns the feel of the location. Locations like Terre Haute, Ind., or in Lebanon, Ill., and their possible beauty can be seen on his canvases.

Many of his pieces featured at the McKendree Gallery of Art are colorful, textured and use the same location but with a slight shift in time or angle. At first it may seem odd to see the same scene but walking around and coming back to the pieces, the small detailed changes start to show and the feeling of the space, even if slight, comes to life.

After leaving mining construction, Neary’s next job was for a company that made whack-a-moles and carnival games. He painted instructional signs for the games. Soon after, his career took off and he got a job with a corporation that made billboards and signs for many different things. In Terre Haute, there was a semi-final for the Miss Indiana contest as a preliminary for Miss America. On a 25 by 12-foot trailer was a large picture of one of the contestants and late at night, someone had spray-painted a mustache, glasses and a few blacked-out teeth on her. “They sent me out to do a little cosmetic surgery. I took my paints out there and fixed her. No one was the wiser.”

Painting large murals would scare some people because of working atop tall ladders or the mere size of the works but to Neary it was great work and, in a field where work may be limited, it was opportunity. “I liked painting these pictorial things that was basically copying pictures but 14 feet tall and four feet wide.”

His experience took him many places that were unique and interesting. Once, he was sent to paint at a baseball field which usually sat large crowds but now only he was there. Neary took advantage of the opportunity and “had my lunch on second base. I laid out in the outfield and took a nap.” It was a dream that many baseball fans have probably had but could never achieve.

“After that I did some teaching in a state prison.” When the government would fund such programs, Neary spent his time with convicts teaching them art appreciation, art history and having some good conversations throughout. Neary felt that it was good for everyone. However, Terre Haute pulled the funding for the program to try to give grant money to students the state felt needed the money more than convicted criminals, despite the statistical evidence that proved programs like Neary’s reduced the rate of convicts returning to prison.

With such experience many may wonder why Lebanon is where he calls home. Neary’s wife is Amy MacLennon, Associate Professor of Art at McKendree University, and they moved here together when she began working for the university. “I definitely have the sweeter end of the deal, though teaching would be nice, too,” he says. His days start with reading the paper and making coffee before going off to his home studio and working until lunch, after which it is back to the studio before he makes dinner, reads a book and then goes to bed. Being in a relationship where one person teaches art and the other does art, Neary reports that he “does most of the cooking.”

Neary’s work has been featured in many galleries just about anywhere he has lived. He is now a member of the Midwest Paint Group which sets up showings for many artists in quite a few interesting locations. Viewing his work or any of the other artists is easy if for some reason the distance is too far to travel; head to their website and click on whomever you find interesting.

Michael Neary has experience in many things from painting to physical labor but decided early in his college career that if he wanted to be successful, he needed to pursue something that engaged him and inspired him to succeed. He had to drop out of college at one point but found himself drawn back to his now profession of art, something that started back in high school when he would find any moment in school to get into the studio. “I’ve always liked doing it, ever since I was a kid. It made me feel engaged,” Neary adds.

What a fascinating essay on a fascinating and talented artist. Thanks so much for your good work on this, Nathan!