By Ashley Hathaway, Contributing Writer

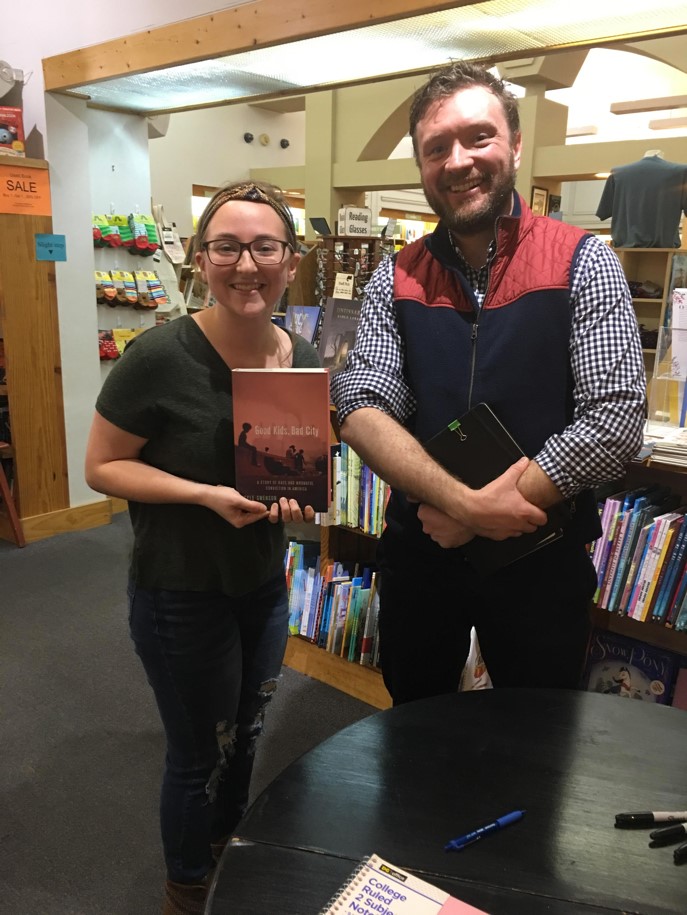

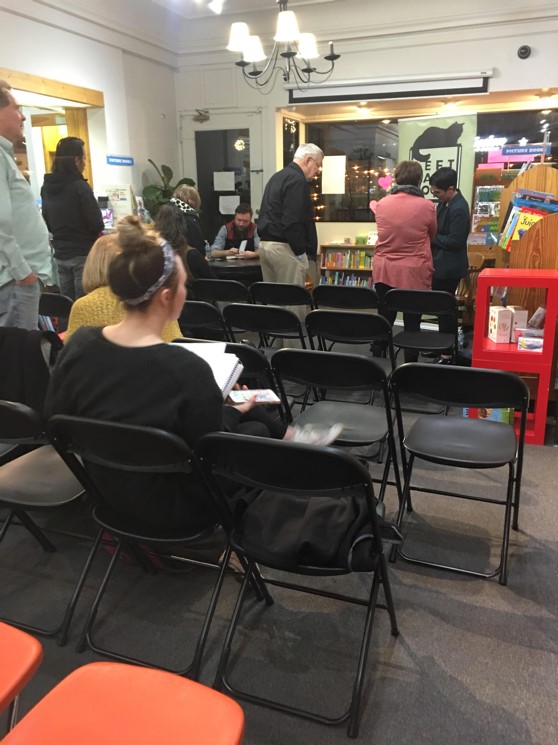

I walked through the doors of Left Banks Books just shy of 7 p.m. on a chilled Monday evening. There were signs plastered throughout the bookstore with the promotion of sales, new releases and classic literature. I weaved my way through shelf upon shelf until I landed in a room with chairs lined up in a small and intimate fashion. In front of the chairs sat award winning journalist Kyle Swenson. As a journalist for The Washington Post and author of “Good Kids, Bad City,” Swenson takes pride in focusing his work in journalism on the criminal justice system in the United States. While people filed in to take their seats in anticipation for the discussion focusing on “Good Kids, Bad City”, Swenson made himself approachable, letting conversations flow even before the event started. With curiosity flooding from guests about Swenson’s time as a journalist and his triumphs as an author, one topic remained the highlight of conversations: wrongful conviction.

As the introductions were made, the chatter began to cease as Swenson took the floor to begin discussing his work on “Good Kids, Bad City.” It was written with the intent to portray the story of Kwame Bridgemean, Wiley Bridgeman and Ricky Jackson: three black men who were wrongfully convicted of a murder charge in 1975 in Cleveland, Ohio. Due to what is believed as systemic racism, the three men spent a combined 106 years behind bars for a crime they did not commit. With the help of Tricia Bushnell, the Executive Director of the Midwest Innocence Project, conversation began to overtake both Swenson and Bushnell while the audience listened closely to the details surrounding “Good Kids, Bad City.”

“In your book, you start by explaining the history of Cleveland. Why did you think it was important to begin with the history of the city?”

“I grew up in Cleveland. I knew that issues surrounding race are a central part of the history the city has, but I needed to know why.”

As Swenson talked, he began to uncover fracturing points in Cleveland’s racial history. With major race riots in the 1960s, and the horrific Glenville shootout in 1968, the tension between blacks and whites has remained prevalent throughout the course of time. According to Swenson, it is crucial to understand this in order to understand how three innocent black men eventually get sentenced for a crime they never committed. In this particular case, systemic racism within the judiciary system led a case with no physical evidence and only a single accusation from Ed Vernon, a 12-year-old boy at the time, to have enough weight to find three men guilty.

While the ruling originally sentenced the Bridgeman brothers and Ricky Jackson to death, the sentencing was later to revoked to life in prison with the possibility of parole. In 2003, Kwame Bridgeman was released from prison on parole and soon found his way to Swenson to ask for assistance in proving their innocence.

“When I first met with Kwame, I believed him for the most part. But there was 1% of me that was holding back. I just kept thinking, how could someone spend decades in prison for a crime they did not commit?”

Despite his slight apprehension, Swenson took on the story with an open mind and enthusiasm. With a long fight to gather trial transcripts from Cleveland as well as the homicide report, Swenson began gathering the information that he needed to begin proving that Kwame, Wiley and Ricky were innocent.

With the homicide report available to him, Swenson noticed that there was a huge part that was missing: there was no mention of Ed Vernon being in the area at the time of the crime. This raised a question: how could Ed accuse these three men of committing the crime if he did not even see the crime?

The gathering of this information among much more led Swenson to release an article that was published in the Cleveland Scene magazine in 2011. Swenson had high expectations for the way this article would be perceived and was soon disappointed when there was little response. It didn’t immediately allow the men to walk free like Swenson had imagined, but it did engage the efforts of the Ohio Innocence Project to pick up the case again. This led to a reopening of the case against Ricky Jackson.

“Good Kids, Bad City” goes into the grueling details of the cases that ended in a revoking of all charges that were originally made against the Bridgeman brothers and Ricky Jackson. After spending a combined 106 years in prison, the three walked free in 2014. Swenson was able to be there when they walked free for the first time in decades.

“The questions people were asking them were just stupid. They were asking things like ‘What is your first meal going to be?’, when in fact they should have been asking ‘Wait, how the hell did this happen?’”

This happens more than we would like to think. As a middle-class white female, I have never had to come face-to-face with the injustices that lie within our criminal justice system. However, cases like this along with many others prove that there is systemic racism that is deeply rooted within our judiciary systems. According to Tricia Bushnell, the Midwest Innocence Project alone is currently dealing with over 700 cases, and 80% of the cases deal with African American clients.

“These are issues that plague American cities,” said Swenson, but how do we combat these incredibly complex issues? In Swenson’s opinion, we must pay attention to local prosecutor elections, as well as hold the Conviction Integrity Units in our city’s accountable. While the issue is deeply rooted, it is possible to begin making changes by being aware and active.

It seems as if we have burned out the outrage around these issues because we have been living with it for so long, but we must attempt to stray from this. Showing outrage towards issues that are longing for a cry of help is crucial. While there are many cases that show utter disgrace, there are also cases that show that justice is possible, which “Good Kids, Bady City” displays with clarity.

People have been responding to “Good Kids, Bad City” with positivity and curiosity, with discussions beginning to flow all around the country. This is a step in the right direction and Swenson talks about this with pride.

As the conversation began to slow between the audience and Swenson, it was clear to me that with the information I had gained from the discussion I had to begin my own fight against these injustices. By reading “Good Kids, Bad City” and by being aware of what my surrounding communities face, I am better upholding my responsibility to my peers and fellow citizens.