Alarums, Excursions and Politics in Thailand

BY NATALIE VAN BOOVEN

_____________________________________

Many people know Thailand for its elephants, its extremely spicy food and its style of kickboxing. Now, its political crisis joins the list. In the latest development, after Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra met with the Election Council, the government decided to hold elections on Feb. 2, notwithstanding the protests, violence and boycotts by the opposition that have racked the country for the last several months. Just the week before, when anti-government protesters overran polling stations in an attempt to stop early voters, one person was killed and about 12 others were hurt—just a few of the 10 casualties and the 577 people hurt since Nov. 30.

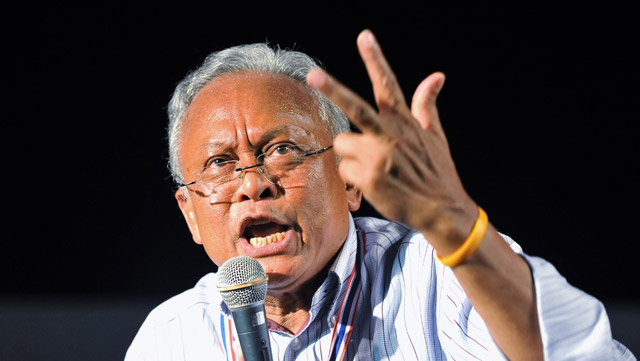

Source: Google Images

On the other side, former deputy Prime Minister Suthep Thaugsuban wants to suspend the constitution to let an unelected “people’s council” lead the country. As he and his followers see it, Yingluck Shinawatra is a puppet leader running a bogus government. Orders are not being given by her, but by her older brother, Thaksin Shinawatra, who was ousted bloodlessly in 2006 and is currently in self-imposed exile in Dubai. In any case, the “yellow shirts” (who support Thailand’s monarchy) have lost many elections to the “red shirts” (who support what the Shinawatras have done for Thailand’s people); and the likelihood of the red shirts winning again will only bring the country closer to obliteration.

This crisis is only the most recent of Thailand’s political troubles; others include the crises of 2008-10 and 2005-06. Grasping the full magnitude of the situation, however, means looking at the relationship between the King and the people, and that requires looking at history, albeit in a telescoped way.

Source: Google Images

Thailand’s recent history can be broken down into four general periods. The first period began in 1855, when King Rama IV signed the Bowring Treaty, which forced Siam to open itself up to the world and to change from a feudal state to a market economy. (Siam would not be called Thailand until 1939—except for the period from 1945-49, when it answered to Siam again.) Siam was the only Southeast Asian country to resist European colonizing, and Rama IV was instrumental in the process of maintaining that freedom. Even now, Thais use the phrase “land of the free” to celebrate this fact.

The second period began in 1932, when a group of lawyers and soldiers demanded a constitution, forcing Thailand to change from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy, which it is to this day. Constitutions are not guarantees of the people’s freedoms and duties, as they are in the West. They are guarantees of the regime’s power and longevity, and 16 constitutions have been drafted—with as many coalition governments—since 1947. The reason for this is Thailand’s centuries-old patronage system, which functions similarly to a civilian oligarchy and is difficult to explain concisely.

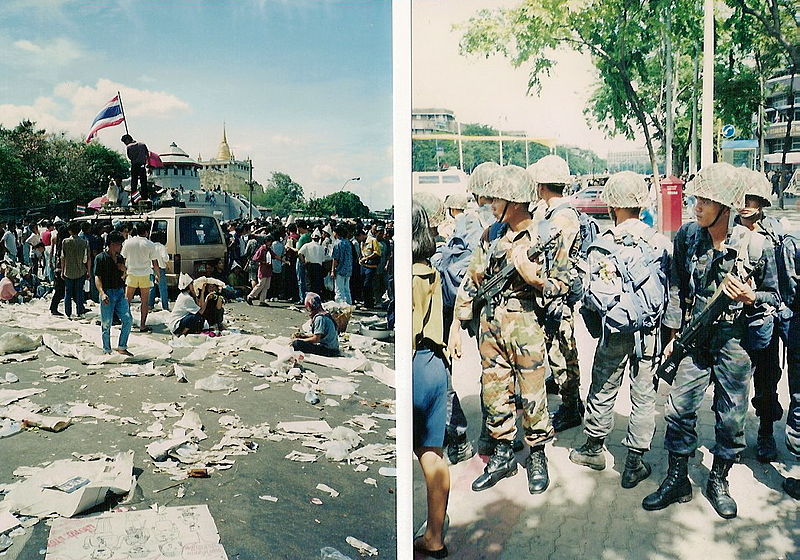

In 1973, tens of thousands of university students protested the government’s flagrant corruption (a side effect of the patronage system), marking the first-ever people’s demonstration. The next three years of dissonance between the upper class and the middle class exploded in the Six October Massacre of 1976, after which Thais began rethinking and clarifying the links between who ruled and who was ruled. The 1978 constitution helped the healing process, reconciling with the students who joined Thailand’s Communist insurgency after the Massacre. It also included a timetable for the government’s transition from military control to civilian control, though political reform to that end only happened after the Black May protest of 1992, and finally solidified in the 1997 constitution, which marks the third period.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Unlike those of its 15 predecessors, most of the provisions in the 1997 constitution aim to break the cycle of military coups and curtail the patronage system. Innovations include making vote buying unfeasible through compulsory voting, guaranteeing 40 human rights, separating the executive and legislative branches even more than in the past, decentralizing the government and increasing checks and balances. The document was praised for its political reforms, its easy amendment process, its protection of human rights and the amount of participation that occurred while it was being drafted. Its weaknesses included not clarifying the King’s role in politics and its being “a charter without any constitutional or theoretical foundation,” according to Thammasat University law lecturer Kittisak Prokati.

Jan. 2001’s general election, the first conducted under the 1997 constitution, was applauded as the least corrupt election in Thailand’s history. The two biggest names were Thaksin Shinawatra, representing the Thak Rak Thai party, and Chuan Leekpai, representing the Democrat party. Shinawatra won, and Thailand has never been the same.

If King Rama IV can be compared to George Washington (both men founded a modern nation and are renowned in each country), then Thaksin Shinawatra can be compared to Abraham Lincoln (both men sent their modern nations in a fundamentally new direction). For a start, Shinawatra was Thailand’s first Prime Minister to serve a full term in office; he used that term to improve the lives of farmers and workers, who constitute the biggest chunk of 80 million people. He introduced universal healthcare, allowing all citizens to pay 30 baht (ca. $1 USD) for medical care. He continued the 1997 constitution’s mandate to decentralize education and launched a student-loan program. Perhaps the most visible reform was the streamlining of the government (the “big bang”), the first such reorganization in 100 years.

That is not to say that Shinawatra was universally loved; in fact, he was highly controversial. He was undiplomatic toward foreign leaders and the world at large; during the widely criticized war on drugs, he said in an interview, “The UN is not my father. I am not worried about any UN visit to Thailand on this issue.”

Many schools accrued debt implementing his plan to ensure at least one high-quality school in each district (the “One District, One Dream School” project). The most trouble during his tenure, and the trouble that got him ousted in the first place, concerned the family-owned Shin Corp.

***

note: The news on Thailand will be continually updated as time progresses.

[…] to Thailand Part 1 prior to […]