BY NATALIE VAN BOOVEN

Google Images

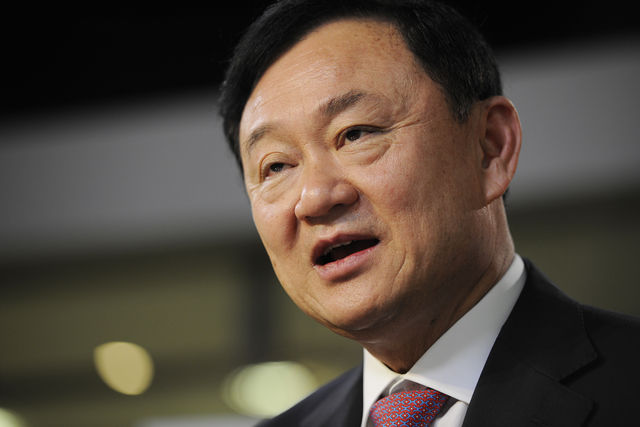

Sept. 19, 2006 was a watershed day in Thailand. On that day, after crossing the line once too often, Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra was ousted in a military coup.

Trouble began for Shinawatra almost from the moment he took office. The first of many disputes—and the first major test for the new constitution—occurred just after his Thai Rak Thai party secured 248/500 parliament seats (three short of an absolute majority) in the 2001 general election. Lauded as Thailand’s most democratic constitution to that date, the 1997 Constitution contained many features designed to protect the people’s increasing power. For example, it mandated an Administrative Court to guard against bureaucratic abuse and a Constitutional Court to deal with constitutional conflicts. Yet the courts’ novel format (that is, giving judges direct authority instead of just letting them examine arguments) meant few judges realized what tectonic impact they could (indeed, would) have.

Returning to Shinawatra, in keeping with the provisos laid down in the 1997 Constitution, he had to disclose his assets upon being elected—but he failed to disclose all of them, having allegedly transferred some assets to his driver and maid without their knowledge. A guilty verdict would have forbidden him from taking part in politics for five years; however, his popularity among the Thai people, as well as his tearful insistence that his failure to disclose was due to clerical gaffes, forced the judges’ hands. By a contentious-to-this-day vote of 8-7, they declared him “not guilty.”

With the court’s verdict out of the way, Shinawatra was free to become one of Thailand’s most distinctive Prime Ministers. Above all else, he devised his policies for the benefit of the rural poor, who comprise the biggest percentage of some 67 million people.

Two of the most important policies concerned health care and the economy. On the health-care front, Shinawatra inaugurated subsidized universal health care. Doctor visits cost only 30 Thai baht (ca. $1 USD) each under this plan, and everyone was covered; previously, most Thais lacked health insurance as well as adequate access to health care. Although access to health care jumped from 76 percent to 96 percent, many doctors resented their increased workloads and found higher-paying jobs, forcing some hospitals to find other sources of revenue and leading to a surge in medical tourism. In 2005, Thailand earned ฿33 billion THB (ca. $85 million USD in 2005) from 1.3 million foreign patients. Locally, nearly half the enrollees were unhappy with the service from subsidized facilities; many preferred getting their medicine from the pharmacies instead of from the facilities. By the time of the coup, universal health care had put the government nearly ฿8 billion THB (ca. $212 million USD in 2006) in debt.

On the economic front, of the many programs Shinawatra launched (e.g. microloans to let taxi drivers eventually own their vehicles), the most important program was easily One Tambon One Product (OTOP). After provinces and districts, tambon (sub-districts) are Thailand’s largest units of local government; every district has 8-10 tambon, adding up to about 7200 tambon in all. The point of OTOP is to reinforce local culture, inspired as it was by Japan’s One Village One Product initiative. Accordingly, each tambon focuses on something it makes well, and that something could be furniture, handicrafts, pottery, food, textiles, flowers, metalwork, etc. Besides enlivening interest in local culture, OTOP has allowed Thais to invigorate the economy by selling their goods to the world. For a while during the coup, OTOP was canceled; unlike universal health care, however, it was soon reinstated.

If Shinawatra’s first term as Prime Minister was remarkable for bringing attention to a previously ignored group of people, then his aborted second term was notable for causing the schism that Thai politics exhibits to this day. By the end of his first term, his influence was such that the TRT secured 374/500 seats in Parliament—just one seat away from exactly 75 percent— in the 2005 general election. For the most part, life in Thailand flowed smoothly for the next seven months. Then, in Sept., the already heady discord between Shinawatra and media tycoon Sondhi Limthongkul burst when the latter accused the former of violating the ecclesiastical power of King Bhumibol Adulyadej. The specific charge was that, when the government appointed a new Supreme Patriarch to replace the sick one already in power, it overstepped its boundaries; Thai religious law stipulates that only the King can appoint Supreme Patriarchs, who must be nominated by the Supreme Sangha Council.

Shinawatra’s term did not get any easier. On Sept. 27, when the Manager Daily newspaper (started by Limthongkul) published a sermon made by a Buddhist monk named Luang Ta Maha Bua, who was now one of Shinawatra’s most vehement critics. The fact that monks are above criticism in Thailand only amplified the controversy of Bua’s disapproval. Shinawatra had to sue the newspaper, not the monk, for ฿500 million THB (ca. $15.5 million USD), which lead to accusations of silencing the press. In the subsequent lawsuit, Limthongkul’s lawyers argued that Shinawatra was wrong to single out the Manager Daily because all the newspapers published Bua’s sermon; while Shinawatra’s lawyers argued not only that the other newspapers only published excerpts of Bua’s sermon, but also that the Manager Daily published the sermon itself under a vilifying headline. Ultimately, civil-rights lawyer Thongbai Thongpo said the lawsuit was not “an attack on freedom of the press.”

Other controversies (e.g. the Temple of the Emerald Buddha incident, in which Manager Daily’s website alleged that, by presiding over a ceremony at Thai Buddhism’s holiest site, Shinawatra took away the King’s power) peppered Shinawatra’s second term, but he survived them all. Then came the year 2006.

To humor the Thai Telecommunication Act, enacted on Jan. 20, the Shinawatra family sold its 49-percent share of Shin Corporation to Temasek Holdings, owned by the Singaporean government. Under the earlier Telecom Business Law, enacted in Nov. 2001, foreign investment was limited to 25 percent of a company’s portfolio. Shin Corp.’s competitors, DTAC (owned 40 percent by Norway’s Telenor) and TA Orange (owned 49 percent by France’s Orange S. A.), wanted to increase that limit because they believed it stifled foreign investment.

The transaction itself happened on Jan. 23, when the family’s share was sold to two of Temasek Holdings’ nominees, Aspen Holdings and Cedar Holdings. Criticism of the sale came from the facts that (1) the law was changed just before the sale happened, (2) a Thai company was sold to a Singaporean company and (3) the transaction was exempt from the capital gains tax. This last item was significant because the families of Shinawatra and his wife Potjaman (née Damapong) earned about ฿73 billion THB (ca. $1.9 billion USD) from the sale.

The sale was the last straw for the Thai people, who by now had long been concerned with how Shinawatra used his power. His dissolution of the House of Representatives in Apr., following the 2006 general election, only jelled the people’s frustration with him. After the King intervened (something he rarely does), calling out the elections as the sham they were, the Constitutional Court ordered new elections to be held in Oct. Unfortunately, Army Commander General Sonthi Boonyaratglin beat the courts to the punch on Sept. 19, while Shinawatra spoke at the United Nations’ Council on Foreign Relations. As for the TRT, the Constitutional Tribunal dissolved it on May 30, 2007; but it has since reincarnated three times, the newest of which is under the command of Yingluck Shinawatra.