Katherine Gemmingen, Head Copyeditor

Featured image from CNN

What better way is there to start off the spring semester than with a talk about the impending doom that describes the current state of foreign relations between the United States and Iran? Through the first Brown Bag lecture of the semester on last Wednesday, January 15, Dr. Brian Frederking did his part to shine the light of understanding on what exactly is the relationship between Iran and the US.

For those of you who are unsure of who this professor brave enough to dive into the Iran issue is, Dr. Frederking is a political science professor here at McKendree. As a political science major myself, I have had many classes with him and (rather unfortunately) find myself enthralled by all things political. Dr. Frederking typically teaches the political science classes that deal more with international relations than American politics. Background aside, Dr. Frederking is certainly the authority on campus to attempt to explain the complexities of foreign relations between these two nations.

In political science classes, Dr. Frederking often uses the term “US package deal” to explain American approaches to foreign relations. This package deal includes things like democratic norms (such as rights and freedoms), alliances in exchange for protection, and general promotion of Western ideals. This approach has been in effect since 1945, following the end of World War II and the creation of the United Nations. Dr. Frederking explained that many of the elements of this package deal, like alliances, trade, international law, international organizations, democracy, and human rights have been the backbone of every presidential administration’s foreign policy since 1945. Until 2016, this was the American approach to international relations, but now, Donald Trump is the first president to reject this approach. This is an important point that Dr. Frederking comes back to at the end of his talk.

Following his explanation of the US package deal, Dr. Frederking elaborated on the role of Iran in Middle East politics. Iran is one of the larger states in the Middle East, as you can see on the map below, and it plays a significant cultural role in the area. Most of the countries in this region are majority Muslim, meaning believers of Islam, but they are split over two sects of Islam. One sect of Islam, Shia or Shiite, is more dominant in Iran. Because Iran is the only true theocratic state, meaning that it is fundamentalist Islamic and ruled by a religious government, hence its official name being the Islamic Republic of Iran, it is the leader of the states that are predominantly Shia Muslims; these states are the minority of the two sects. Iraq, Assad’s Syria, Lebanon’s Hezbollah, and Yemen’s Houthis are all part of this Shia minority led by Iran.

The other Islamic sect is the Sunnis. Countries like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Turkey, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and other Gulf states are majority Sunni. Groups like Al Qaeda, ISIS, Hamas, and the Taliban are also Sunni Muslim. These states and groups are the majority in the region, so Iran being the minority leader places the country in a unique situation.

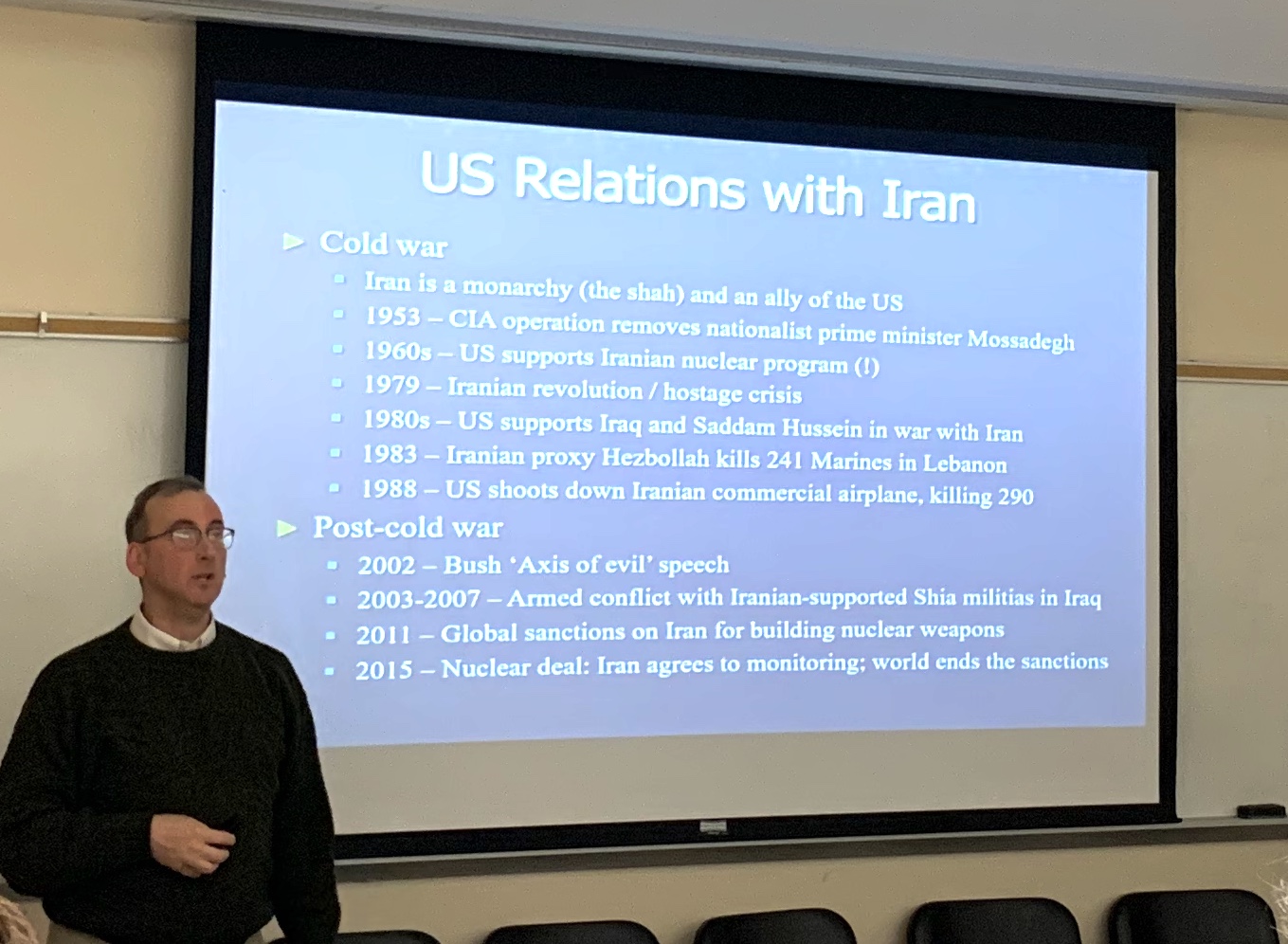

Following this explanation of Iran’s role in the Middle East, Dr. Frederking went through a brief history of relations between the US and Iran, starting with the cold war era. During this period, Iran was a monarchy and ally of the United States. The US actually supported the creation of Iran’s nuclear program in the 1960s, which is quite the twist of irony. The relationship between the two states faced its biggest shift with the Iranian Revolution in 1979, which is also when the Iranian nuclear program ended due to nuclear weapons being inherently anti-Islamic. Relations were further strained by the Iranian hostage crisis.

After the cold war era, US relations with Iran became even more complex. George W. Bush’s 2002 “axis of evil” speech placed Iran and the US on opposite ends, and the US embarked on armed conflict with Iranian-backed Shia militias in Iraq from 2003 to 2007. Although Iran had ended its nuclear program during the Iranian Revolution, the program was restarted later. Global sanctions on Iran were implemented in 2011 as a response to the nation building nuclear weapons. In 2015, sanctions ended with the infamous nuclear deal that established monitoring agreements.

This nuclear deal was widely considered a success by some and a huge mistake by others. It established that Iran would be subject to monitoring of its nuclear program and that the state would not create more weapons. Dr. Frederking keenly pointed out that this deal was also a global agreement, not just one between Iran and the United States. Other nations part of the deal verified that Iran was indeed in compliance with the deal, but Donald Trump wanted to exit the deal in 2017. He was finally able to pull the US out of the deal in 2018, despite the fact that Iran was still complying with the deal. No other states have withdrawn from the deal. Trump also designated the Revolutionary Guard, which is essentially the military of Iran, as a terrorist organization.

Even more recently, Donald Trump ordered the assassination of Iran’s top general, Soleimani. Dr. Frederking made the analogy that killing Soleimani would likely have been the equivalent of if Dwight D. Eisenhower had been assassinated following World War II. He also explained that this action undermines the package deal in three distinct ways. One of the big elements of the package deal is the participation in alliances and international organizations (such as the United Nations, United Nations Security Council, NATO, etc.). Trump violated this norm by not notifying or consulting with allies. Secondly, he violated norms of democracy by failing to consult with or notify Congress. Finally, Trump’s order of assassination violated international law by violating rules on use of force, the territorial integrity of Iraq, and the sovereign immunity of Iran.

For a lot of us students here at McKendree, we grew up during the times of American involvement in Iraq and other areas of the Middle East. It has sort of always been understood that we are supposed to dislike and distrust the region, but the relationship is rarely spelled out in terms of actual consequences. Dr. Frederking began to wrap up his presentation by elaborating on some of the potential consequences that are likely to occur following the assassination of General Soleimani.

The assassination places the US in diplomatic isolation; Dr. Frederking’s previous points about the failure to consult with or even notify US allies results in such isolation since we are the only country to back out of the nuclear deal. Since the US has opted out of the treaty, its legitimacy has been hurt, so Iran has begun to ignore certain parts of the deal that it is supposed to comply with. There has also been increased Iranian influence in Iraq at the same time that NATO allies are leaving Iraq. Many Americans wish to see our own military forces withdrawn from Iraq, but much of the reason troops are still present is to prevent the resurgence of ISIS in Iraq, and this possible comeback is made more likely as other nations pull out their troops. Dr. Frederking also pointed out that there will inevitably be future attacks by Iranian proxies on US forces and allies.

As with most Brown Bag lectures, Dr. Frederking concluded by answering a few questions from the audience. Most of these questions were focused on what this all means for Americans and if we are truly headed to another world war. Dr. Frederking spoke plainly and said that it would not be a world war since the US does not exactly have any allies in this conflict.

Some of my fellow political science students are probably as familiar as I am with Dr. Frederking’s reactions to difficult questions such as those posed by the audience. He scrunches up his face, kind of covers it with his hands, and chuckles a bit. We were not lacking that reaction in the Brown Bag, and it always serves as a bit of comfort since McKendree’s expert on foreign policy has not yet lost all hope.